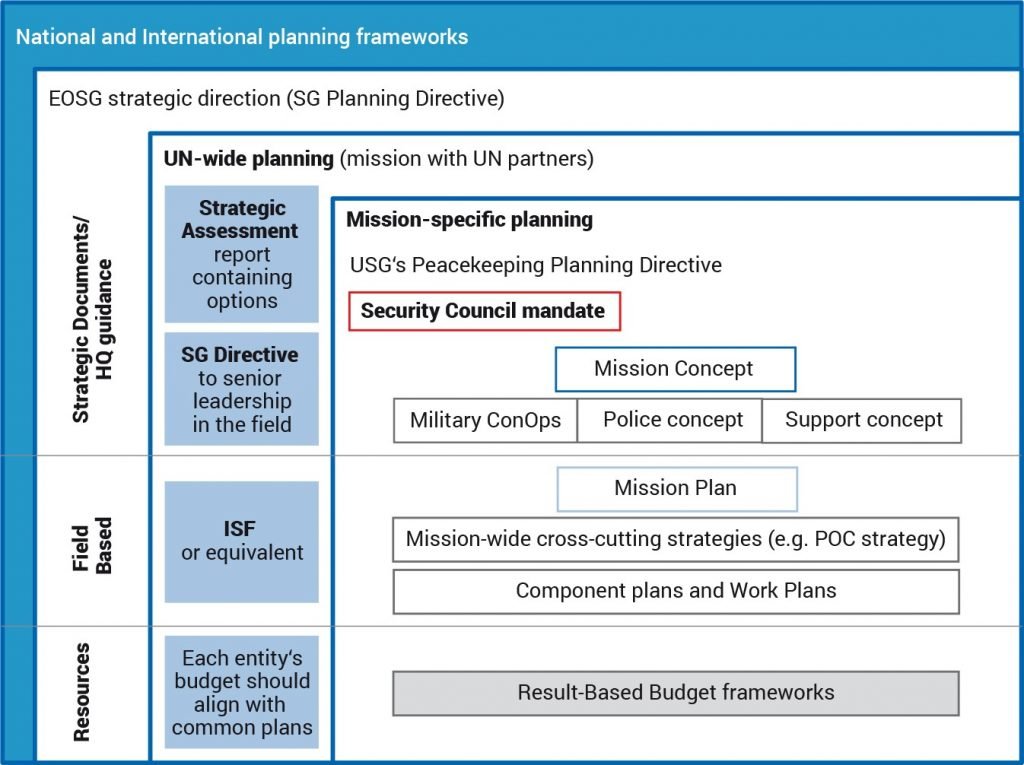

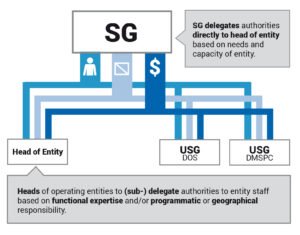

An MLT needs to understand how UN integrated planning works. This includes how planning interacts with the process of designing a mandate. It also touches on relations between UNHQ and the field.

There will be different approaches to planning within any integrated mission. The most obvious may be between the military/police and civilian components. The MLT should encourage flexible planning processes via close interaction and information sharing.

Each UN field presence should also have standing coordination arrangements. The aim of these arrangements is to bring together the UN system. This makes strategic direction and oversight possible. And it focuses the joint efforts of the Organization to build peace in the host country.

Integrated or joint planning structures will vary from one mission to another. This reflects the fact that UN operations call for varying levels of coordination. It is also in line with the principle that “form follows function”.

When the MLT does not drive planning, the unity of purpose of the mission becomes incoherent. Its mission support component (budgetary and logistical resources) struggles to provide timely support. This is why the MLT’s buy-in and active engagement is essential. At the very least, the MLT must give overarching planning direction. This enables a mission to cascade its planning process down through all components. This then forms the basis of a mission plan.

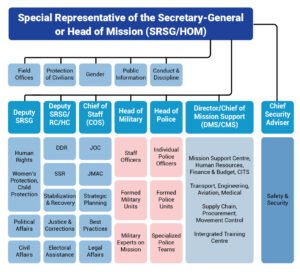

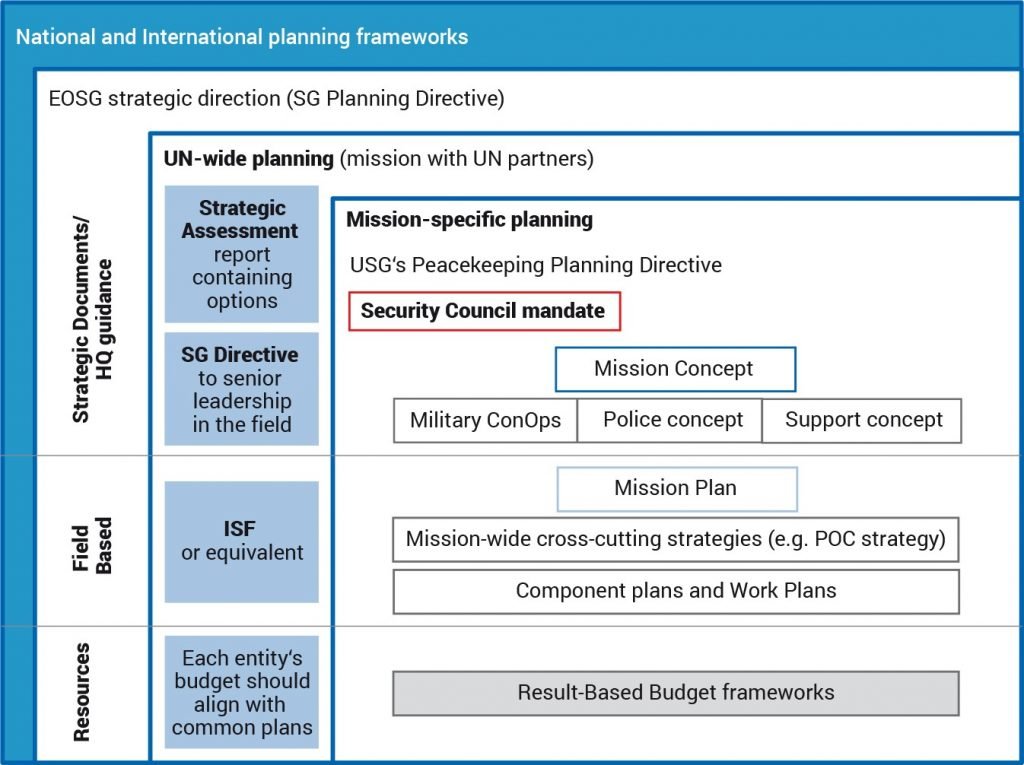

Coordination should fulfil key strategic and operational functions. Strategic planners in UN entities must have a shared understanding on this point. This understanding relates to their purposes, core tasks, and team composition. The Joint or Integrated Planning Unit helps ensure a mission-wide planning structure. Figure 2.2 explains this structure.

Effective and creative use of assessment and planning tools

The UN makes use of an integrated assessment planning (IAP) framework. An IAP is any UN analytical process that has implications for more than one UN entity. There are nine guiding principles of IAP:

- Inclusivity. Planning must involve the mission, the UNCT, and UNHQ.

- Form follows function. A UN presence reflects specific requirements, circumstances and mandates. It can thus take different forms.

- Comparative advantage. The UN should assign tasks to the entities best equipped to carry them out.

- Flexibility based on context. The mission should adapt assessment and planning exercises to each situation. This calls for analysis of the drivers of peace and conflict.

- National ownership. This is an essential precondition for the sustainability of peace.

- A clear UN role in relation to other actors.

- Recognition of the diversity of UN mandates and

- Upfront analysis of risks and benefits.

- Mainstreaming. Processes should reflect UN policies (eg on human rights, gender, child protection).

UN DPKO Policy on Integrated Assessment and Planning

To ensure UN coherence, each mission should develop an Integrated Strategic Framework (ISF). The ISF should reflect a shared vision of the UN’s strategic objectives. It should set out agreed results and timelines. It should also specify how to ensure efficiency in tasks that consolidate peace. Other UN planning frameworks (e.g. an UNSDCF) can serve as the ISF.

The purpose of an ISF is to:

- bring together the UN system around a common set of agreed peacebuilding priorities;

- identify common priorities, and prioritize agreed activities;

- facilitate a shift in priorities and/or resources, as required; and

- allow for regular stocktaking by senior managers.

The ISF should focus on peace consolidation priorities unique to the mission area. A mission may involve political and sequenced activities by many UN actors. This means that many typical mandated tasks are challenging and time-consuming. Examples include DDR, SSR, the rule of law, and return and reintegration of IDPs and refugees. An ISF helps create clarity and establish priorities and an accountability framework.

Mission planners should be aware of other assessment and planning processes. They should also create substantive linkages with the ISF wherever possible. Such processes may include a Humanitarian Response Plan.

Comprehensive Performance Assessment System

The UN launched its CPAS for Peacekeeping Operations in 2018. The aim was to provide peacekeeping missions with a tool to measure their impact. The system forms part of the Integrated Performance Assessment Framework.

CPAS is a context and mission-specific planning, monitoring and evaluation tool. It helps translate mission objectives into components and work plans. It enables the MLT to pursue activities that have a meaningful impact and reduce those that do not.

CPAS is also an iterative and adaptive cycle. The cycle starts with a planning process and ends with adjustments made to future plans. Figure 2.3 explains the process.

PLAN

1) Define priority objectives, 2) Map the context, and 3) Build results framework. In the first step, all components of a mission come together to form a joint understanding of the priority objectives based on the mandate, to map the context, and to build a results-based framework.

PERFORM

4) Implement plan and capture data. As the mission implements the plan, they capture data on the impact of their work.

ASSESS

5) Analyse data to assess impact and effectiveness of mission outputs, and 6) Generate dashboard. The collected data is analysed to assess the impact and effectiveness of the mission outputs. A dashboard is then generated and the performance assessment is presented to senior mission leadership, along with recommendations.

ADJUST

7) Inform strategic decision-making and planning. Based on the data presented in the dashboard, informed strategic decisions and adjustments are made to improve or maintain the missions’ performance.

In large multidimensional missions, the system will generate quarterly performance assessments. This allows a mission to adapt with more agility to fast-changing circumstances. Over time, it helps inform the Secretary-General’s reports to the Security Council. It also feeds into mission reports to the Fifth Committee of the General Assembly.

Context analysis: Drivers of peace and conflict

In recent years, there has been an increased push for data-driven peacekeeping. There are several reasons for this. An analysis of conflict systems allows for integrated planning and operations. It helps identify drivers of peace and conflict. It also helps identify areas where interventions will contribute to peace and security.

Such analysis might include the internal UN Common Country Analysis or external research. For example, an expert workshop may help identify drivers of peace and conflict. At the other end of the scale, the mission might develop a full peace and conflict monitoring system.

UN DPKO Integrated Planning and Assessment Handbook

The mission should integrate the analysis throughout its planning, implementation and follow-up processes. It is thus based on intelligence, dialogue with stakeholders and continuous reassessment. Done well, it can become a key part of developing a political strategy and mission concept. It also provides a method for ensuring the mission applies a “Do No Harm” approach.

Any peace and conflict analysis should include the following four elements:

- A situation, context or profile analysis.

- An analysis of the causal factors of peace and conflict.

- A stakeholder or actor analysis.

- A peace and conflict dynamics analysis.

Prioritization and sequencing

In the early post-conflict period, urgent peacebuilding objectives must be a priority. The challenge is to identify which activities best serve these objectives. This should reflect the context analysis rather than what specific actors can supply. It is unlikely that a mission can carry out all the required activities at the same time. Prioritization will ensure the optimal use of available resources.

There are clear differences between prioritization and sequencing. Prioritization is a function of the importance of an activity. This does not mean that other activities must wait until a prioritized activity ends. In contrast, sequencing means that one activity should not start until another ends.

Combining the two approaches, an output can have a high priority. But it might be sequenced at a later stage when the context is more conducive to change. For example, a reconciliation process might best begin later, when conditions are favourable.

During the planning stage, the mission should both prioritize and sequence activities. The MLT should give direction on its priorities, while planners provide sequencing options. Legitimate representatives of the host country should take part in these efforts.

The unpredictability of activities on the ground will almost always disrupt planned sequencing. Prioritization and sequencing must remain flexible to adapt to the changing situation. But in their absence, the mission will not know where to put its limited resources. And the influence of external factors will be even more significant and disruptive.

Integrating a gender perspective at every stage

United Nations, ‘Action for Peacekeeping: Declaration of Shared Commitments on UN Peacekeeping Operations’

Any analysis, including planning and actions, must consider the whole population. This means acknowledging variations in living conditions, economic and political life and needs. Thus, a gender perspective must be an integral part of all analysis and planning. A UN peace operation is a critical mechanism for gender equality. If women’s role in peace and security is not progressed, sustainable peace is unlikely.

An active gender perspective is essential across the work of UN peace operations. Without it, missions will only see part of the whole picture. This includes drivers of peace and conflict, threats and opportunities for sustainable peace. Gender expertise within the mission is thus essential. It helps ensure that peacekeeping activities respond to the needs of women and men. It also ensures allocation of resources to support the WPS Agenda within the mission.

Integrating a gender perspective is a mission-wide commitment. It has to start with the MLT.

A gender-responsive analysis considers power dynamics in society. It identifies indicators that serve as early-warning signs of threats to the mission. This is particularly important for missions that have POC as part of their mandate. Such an analysis can enhance the mission’s ability to assess threats and respond to them.

Failure to undertake a gender analysis can have a detrimental long-term impact. It could set back peace processes and future peacebuilding efforts.

Intelligence-based decision making

In UN peace operations, intelligence refers to information related to implementing a mandate. Intelligence data can also inform a peace and conflict analysis, and decision making. Intelligence enables missions to take decisions and enhance the security of all staff.

Peacekeeping intelligence supports a common and coherent operational picture. It provides early warning of imminent threats through good tactical intelligence.

The precise intelligence structure will vary between missions. It depends on the mandate and the resources made available by TCCs.

Using emerging technology

Missions make use of new technologies to varying degree. One example is monitoring and surveillance technologies. New technology can facilitate the implementation of the mission’s mandate. But the MLT should seek advice from experts from all three components on this issue.

A mission primarily uses technology to support decision making and enhanced security. Examples include situational awareness, unmanned aerial vehicles, ground radar and closed-circuit television.

The MLT should coordinate technical issues (e.g. radio frequency) with the host country. But monitoring and surveillance technologies requires careful political management. The MLT must ensure that it remains impartial under international and national laws. A mission must not engage in illegal activity to collect information.