In a UN peace operation, police and military components play key roles in creating a secure and stable environment until the host government can maintain security on its own.

The mission should project strength and credibility, prevent spoilers from undermining peace processes, and partner with the government to reform the security sector. This may involve the legitimate use of force.

Operational Outputs

Warring Factions Separated and Violent Conflict Contained

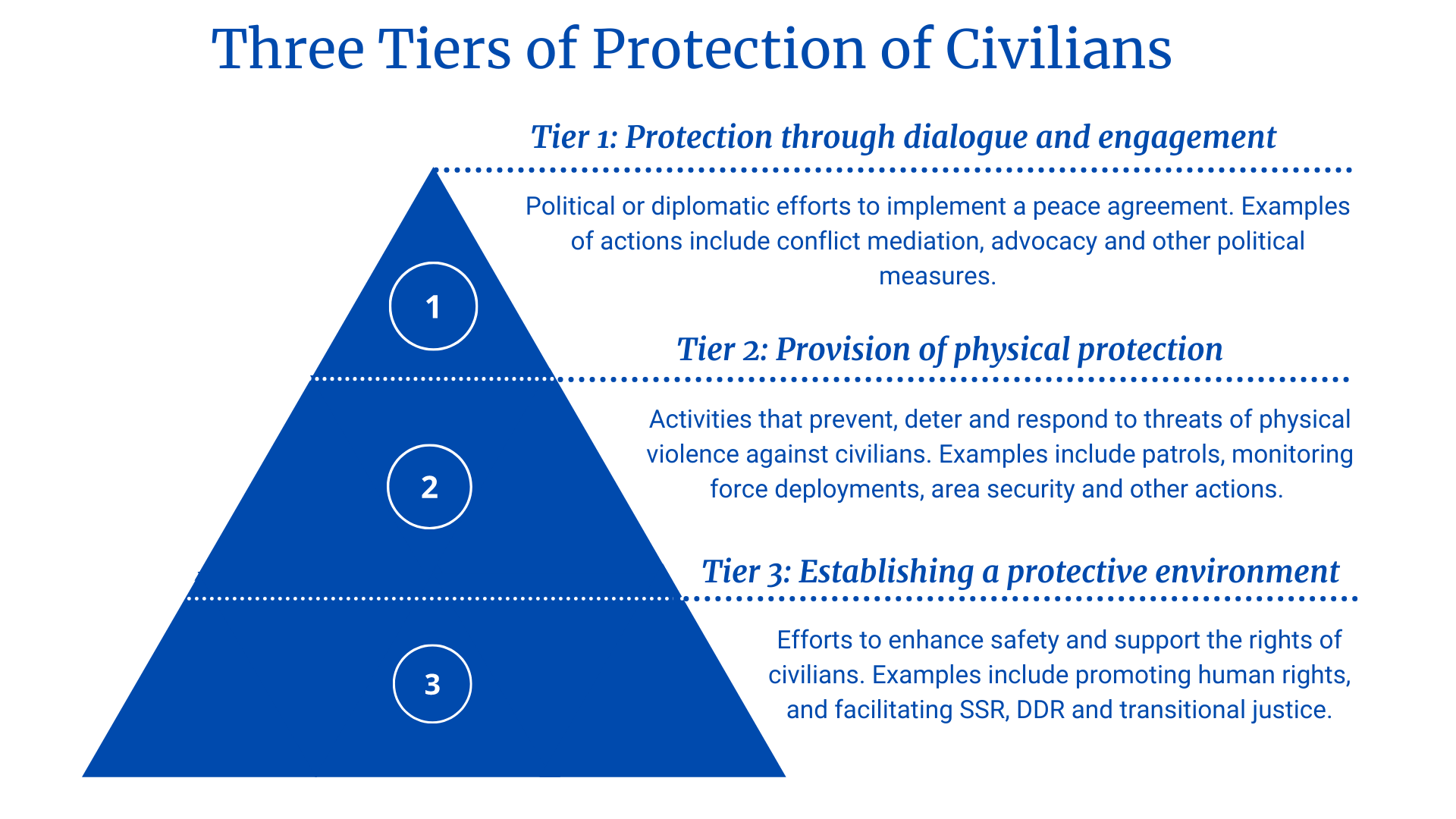

Separating parties to a conflict allows peacekeeping force to monitor their actions. Establishing areas of ...Civilians Protected

Civilians are often targeted during armed conflict. Women, children, refugees, IDPs, minorities and the elderly ...Freedom of Movement Regained and Exercised

The free flow of people and goods leads to the normalisation of daily life and ...Threats from Spoilers Managed

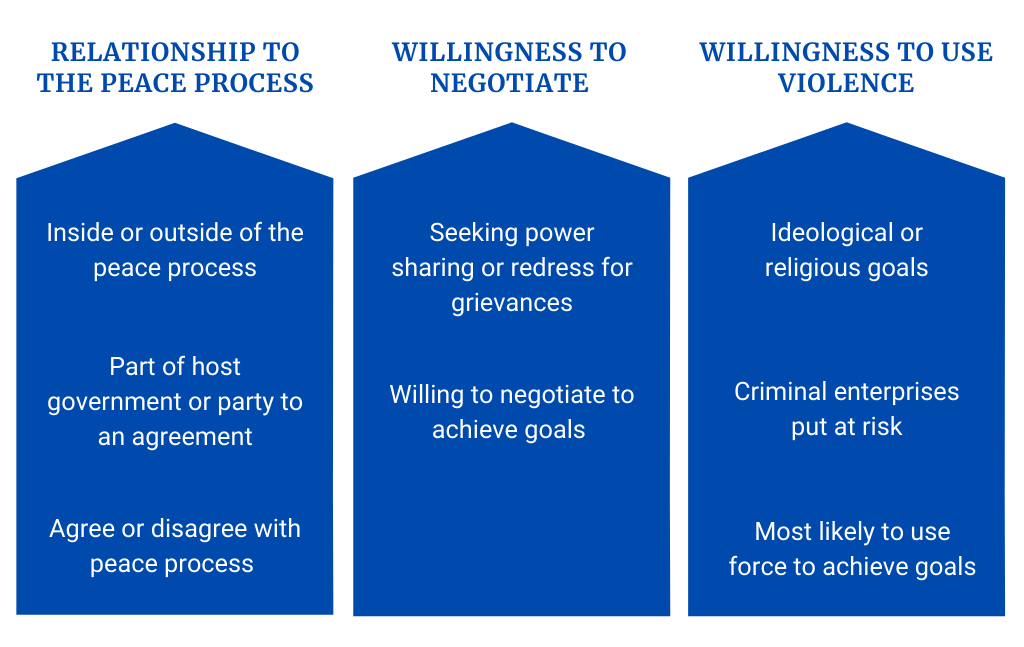

Threats to the peace process come from many sources. This output focuses on the challenges ...Public Order Established

Public disorder is destabilizing. It undercuts efforts to strengthen state security institutions. It is often ...Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Programmes Implemented

Dealing with combatants is a crucial first step towards peace and reconciliation. DDR contributes to ...Definition

In a secure and stable environment, the civilian population can pursue its daily activities in relative safety, free from large-scale hostilities and violence.

In such an environment, there is a reasonable level of public order, the state holds a monopoly over the legitimate use of violence, and the population enjoys physical security and freedom of movement.

In addition, the country’s borders are managed to mitigate the effects of transnational organised crime and to protect against invasion or infiltration.

The use of force

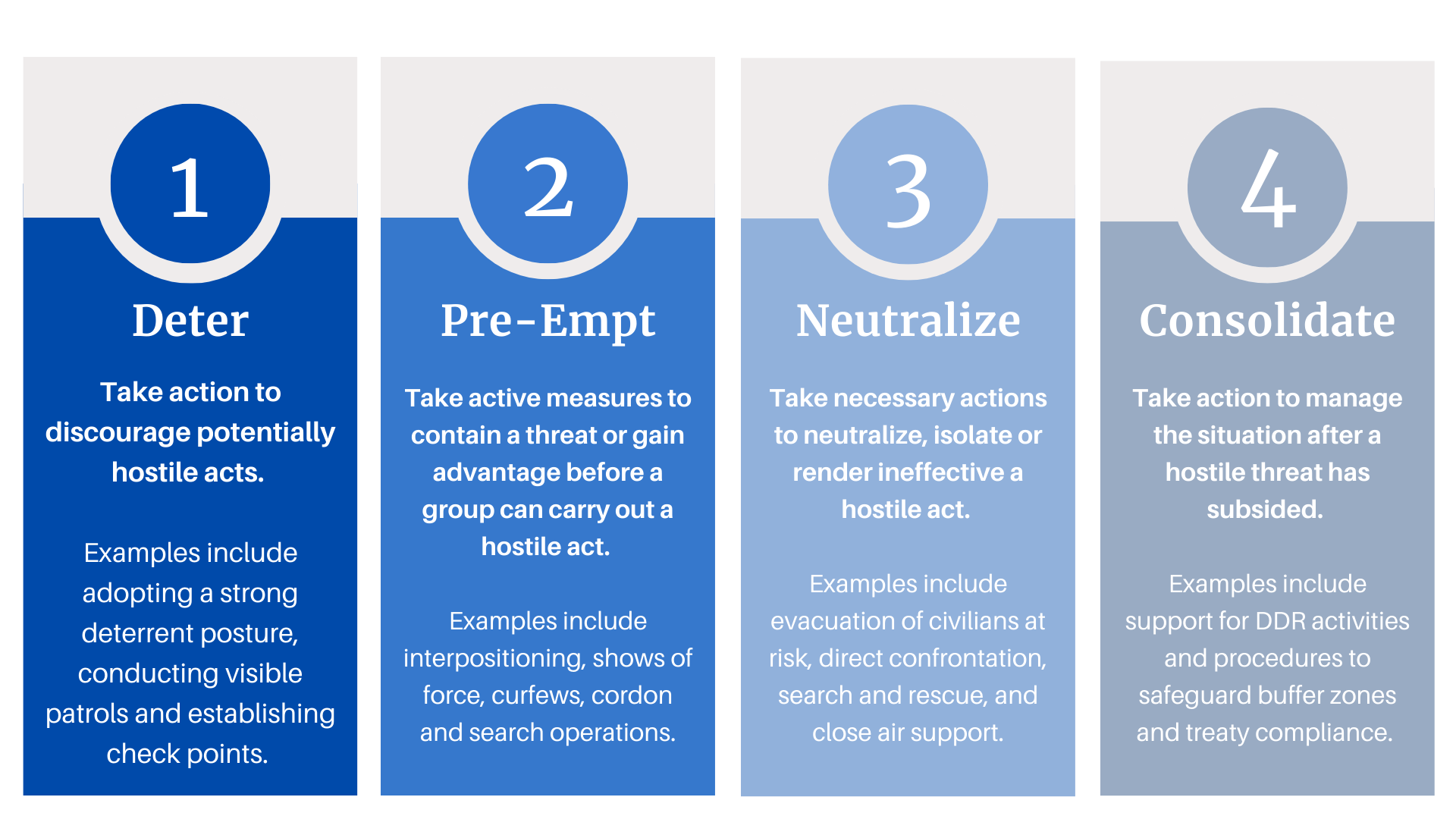

If the MLT determines that force must be used to fulfil its mandated tasks, such use of force must be linked to the desired political outcomes.

The mission should demonstrate a credible, flexible force posture and presence which does not yield to the unlawful use of force by non-state actors.

The use of force should be part of the political strategy of the mission; legal; consistent with the ROE (military) or the Directive on the Use of Force (police); proportionate; critically necessary; and capable of achieving the desired outcome.

Reliable intelligence is essential for the effective, proportionate and judicious use of force.

Preconditions for Success

An agreement forms the basis of the peace process, the implementation of which leads to a sustained settlement of the conflict.

All major parties to the conflict are committed to the peace process.

International/regional partners support the peace process.

TCCs/PCCs remain committed to pledges, which include training, preparation, equipment and willingness to act robustly when needed.

National authorities develop the capacity to address security and stability issues.

Benchmarks

MINUSCA: RED LINES AND THE USE OF FORCE

A critical question for the leadership of a UN peace operation is how far a mission can go in using force, and when it is right to do so. While the grounds for the use of force are likely to be fairly well defined in the mandate (usually in terms of the need to protect civilians, probably also to protect the mission and humanitarian actors, and to defend the mandate) and reflected in the military Concept of Operations and Rules of Engagement, much will depend on the interpretation of, for example, what constitutes a threat to civilians, or when it is justifiable for a mission to defend its mandate by force.

For example, in the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), when certain ex-Seleka groups were threatening to march on Bambari (the second biggest city in the country), the mission decided that its protection of civilians (POC) mandate meant that it could set “red lines”, beyond which armed groups would face the use of force. When some rebels breached these red lines, the mission justified air strikes in terms of protecting civilians.

For example, in the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), when certain ex-Seleka groups were threatening to march on Bambari (the second biggest city in the country), the mission decided that its protection of civilians (POC) mandate meant that it could set “red lines”, beyond which armed groups would face the use of force. When some rebels breached these red lines, the mission justified air strikes in terms of protecting civilians.

UN peace operation must not be a party to the conflict, and the International Committee of the Red Cross, which acts as the guardian of international humanitarian law, was clear that the airstrikes would have compromised the mission’s status were it not for the specific warnings given that this was how we would interpret our POC mandate.

It was important for MINUSCA to have thought through the implications and consequences of the airstrikes. These questions of interpretation are likely to arise during a crisis situation and a mission leader may have little time to decide what they can do. So, having a sound understanding of the limits, and indeed of how far those limits can be stretched, is essential.

Diane Corner, DSRSG, MINUSCA, 2014–17